In the townland of Toberdornan — roughly between Bushmills and Coleraine in the parish of Ballywillin, County Antrim — sits a prominent basalt outcrop named Dunmull Hill. The site is something of a geological, archaeological, and historical marvel, and has served various purposes since ancient times due to its geographic advantage. Writings on the hummock featured in the pages of geological journals in the 19th century because of its beauty, ‘conspicuous’ appearance as the highest hill on the flat landscape, and unique basaltic composition, supposedly formed by the same natural process which created the world-famous Giant’s Causeway, deep in the primordial past.1 One such author, William Richardson, wrote in 1808 — seemingly in agreement with modern scholarship — that from the Giant’s Causeway to the Sperrin Mountains was a huge mass of basalt, formed by volcanic activity, which was eventually splintered by ‘the removal of the contiguous portions of [its] strata, by some powerful agent, of whose operations and modes of acting, we have hitherto obtained little knowledge’.2

It is upon this hummock that an important site of political prestige and religious significance was developed, and which featured in several flashpoints in Ulster’s history.

Ancient and medieval times

Pre-Christian Ireland was dominated by the pagan religion of the druids, which involved a ritual sacrifice system often centred around prominent landmarks such as hills, mountains, or large trees. Dunmull Hill appears to have been one such cultic site. The hilltop bears the remains of a ‘druidical circle’ of stones, recorded as about 1 to 3 feet tall, and is ‘supposed to be an ancient burying-place’.3 On the nearby estate, Beardiville, there was also a ‘druidical altar’, or ‘pagan altar’.4 It is unsurprising that the dramatic rise of this hummock from the flat landscape led to a religious significance.

Several other unique stones have been found on and around the hill. These include a large stone chair, called by locals ‘The Witch’s Cradle’, a bullaun stone (a stone with a large hole or indention in the top) called ‘the Giant’s Head Track’ and a footprint stone called ‘the Giant’s Foot Track’.5 Whether any of these were used in druidic rites is unclear; and there has not been much scholarly consensus on the uses of the bullaun stones all across Ireland, whether that be for domestic use (such as water collecting or food preparation), or as a water receptacle in a cultic context.6

Throughout Ireland, such stones have typically been connected with stories of saints and giants. The bullaun stones, for example, often became known as the baptismal fonts of ancient saints or churches, or hagiographically ascribed to saints, as the places where they had laid their heads to sleep.7 David Craig in his book Landmarks comments that the footprint stone on Dunmull was ‘traditionally associated with a saint’, but, sadly, no other source attests to this.8

However, many such stones across Ireland do not even have a pre-Norman dating (pre-1169 AD), and can be more readily associated with the inauguration rites of Irish clans. The O’Flynns were chiefs of the Uí Thuirtri region up to 1212, likely placing the dating of the fort construction on this site to shortly before this date; indeed, a recent report calls it a ‘pre- C12th stronghold’; and moreover, Sam Henry wrote that after the O’Flynns were ejected from Dunluce, they fled three miles south-east to Revallagh, which neighbours Toberdornan.9

Elizabeth Fitzpatrick notes that ‘according to local tradition, [Dunmull] was the place where Uí Fhloinn [O’Flynn] of Uí Thuirtri was inaugurated’ — as does the Preliminary Survey of the Ancient Monuments of Northern Ireland — which, if true, would likely mean that the bullaun, chair, and footprint stones were part of the ‘inauguration furniture’ for the local O’Flynns.10 Such stones, especially the coronation chairs, are affiliated with inauguration sites all throughout Ireland, particularly in Ulster.11 The Ordinance Survey Memoir for Dunmull also describes ‘the ruins of ancient fences’, and ‘the ruins of sundry enclosures of different shapes’; and Fitzpatrick describes ‘the remains of hut sites, what may have been an oratory, a series of banks and a spring well’, suggesting it was once a developed site with ceremonial facilities and inhabitants.12 According to Fitzpatrick,

Dunmull lies in the boundary area between Tír Eoghain and […] Uí Thuirtri. Having dominated the kingship of northern Airgialla, the Uí Thuirtri fell under the control of Cenél nÉogain in the tenth century. In the […] contraction of Uí Fhloinn to this part of Antrim, Dunmull could [well] have been used as their inauguration place in the later medieval period.13

It therefore seems very likely that Dunmull had become an important inauguration site and centre of power for the O’Flynns in the late-medieval period. Whether the ceremonial stones were of an earlier early-Christian or Druidical origin remains elusive.

Symbolic genealogy

By the late fifteenth century, the Route area was firmly under the control of the MacDonnells, the Earls of Antrim. In 1637, Randall MacDonnell, 2nd Earl of Antrim, made a grand gesture by leasing Dunmull to a historian, which denotes the importance of the hill for its ‘dynastic identity and power’ in the local conscious.14 Fitzpatrick’s book Landscapes of the Learned: Placing Gaelic Literati in Irish Lordships 1300-1600 argues that Irish lords would grant land to literati — ‘poets, lawyers, and harpers’ — as a way of connecting ruling Gaelic chiefs to local historic pedigrees and lands.15 The Earl of Antrim leased the townland of Toberdornan, containing Dunmull (and possibly a mill), to the historiographer Fearfeasa Ó Duibhgeannáin, who was part of the renowned Ó Duibhgeannáin family of historians.16 This gesture — associating ‘literati’ with the ‘formaoil’ or ‘bare-topped hill’ boundary landmarks and their ‘associated prehistoric monuments’, which were a part of many estates — linked the romantic past of Irish mythology and history to the power of the present chief of an area, as a ‘living museum of a chief’s imagined heritage’.17

MacDonnell, in this action, pulled together the ancient pagan past, the Christian past (if the stones’ saintly associations in the local culture were a reality), the renown of previous clans, and the Gaelic ‘renaissance of court culture’, into a powerful message of his authority and right to power over the lands of the area. His earldom was granted by the crown ‘in order that, by the residence of themselves or some of their immediate family, the surrounding country might be more speedily civilized and brought into subjection’ — perhaps the intentional fusion of these historic roots into the symbolism of his authority was implicitly intended to aid this.18

The Dunmull Massacre

The remains of the fort itself were taken by the forces of General Robert Monro in Spring 1642, when they were deployed to Ireland to oppose the Irish Rebellion. Monro’s forces were large, allowing him to attack forts and villages with swiftness, in what could be anachronistically called a ‘scorched earth policy’. His armies moved through Ulster, intending ‘to clear that country of the rebels who daily infested Carrickfergus, Coleraine, Antrim and the other garrisons’.19 While moving through the Route, Monro split his forces in two, sending the regiments of Lord Massareene, Colonel Mungo Campbell, and his nephew Colonel George Monro to scour the river Bann, while he went along the coastline with his own forces.20

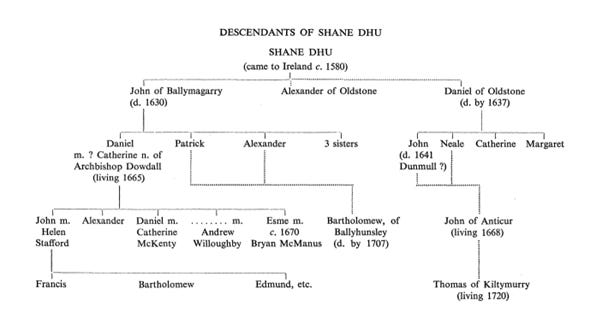

Marching north from Ballymoney, they came across a fort, which was described as being in the middle of a bog, and owned by the Macnaghtens, who were ‘dependent[s]’ of the MacDonnells.21 Indeed, the Macnaghtens had been under the employment of Randall MacDonnell since the arrival of John ‘Shane Dhu’ Macnaghten in the early 1600s — who was an estate manager for MacDonnell — and he, his sons, and grandchildren had land in the Dunluce and Clogh (or, Oldstone) area which they leased from MacDonnell, including Benvarden and Ballybogey.22 The OS Memoirs and the Rev. James O’Laverty both affirm that a hill in Ballybogey is known as ‘Castle Hill’, and O’Laverty affirms that local tradition bears witness to it being the residence of a Macnaghten.23 This is most likely the location of the fort on which Munro’s regiments marched, and it would also have given a straight northward path to Dunmull.24 The Macnaghten fort was said to have been built for protection during the rebellion, and was likely the property of John Macnaghten.25 It has been errantly written in several secondary sources that Dunmull is where the Macnaghten leader took refuge, but the Calendar State Papers for Ireland of 1660-2 and a 1662 pamphlet of rebellion atrocities make clear that the Macnaghten fort was recently built, and that the captured Macnaghten forces were then taken to Dunmull, which had become an encampment for Munro’s regiments.26

The details of the event came to light in 1661-2, when Colonel Alexander Macnaghten, a Scottish Macnaghten, sought to expose the event and get payback against Lord Massareene and co. The Calendar State Papers give us two somewhat contradictory accounts, including Colonel Macnaghten’s initial accusatory testimony against Massareene, followed by Massareene’s account correcting Colonel Macnaghten and giving his version of the events. Below are truncated versions of both accounts.

Colonel Alexander Macnaghten:

In 1642 when Major-General Munroe went into Ireland, marching towards Coleraine, he left Sir Mongo Campbell’s regiment and that of Sir John Clotworthy (now Lord “Mazerine”) at Ballimoney, within two miles whereof there was a fort built by the Macnauchtons called Macnauchton’s fort, for preserving themselves from those which went into the Irish rebellion. They, hearing that some of the army were at Ballymoney, and that Col. Campbell had the command of them, wrote to him, showing that they were there for their own defence and to give obedience to any that had his Majesty’s orders, and they desired a protection that they might come and live in the country. The Lord Mazerine, intercepting the letter, did not deliver it to Col. Campbell, but sent his own Major, as it were from Col. Campbell, showing that he would protect them, and gave them assurance for their lives and goods, whereupon they came out of the fort. But immediately after the said Lord Mazerine caused the fort to be plundered, took the prisoners and kept them till night, but did not bring them near where Col. Campbell was quartered. Yet Col. Campbell’s brother, being on the guard and seeing prisoners taken, asked what they were, and, being informed, told Col. Campbell. Col. Campbell sent to Lord Massereene for an explanation, who assured him that he should the next day have a full account, and that the men and their goods should be delivered to them harmless. “Whereupon Captain Campbell got into his custody fifteen gentlemen, who (for the relation he had to them) kept them that night, not expecting that Mazerine would prejudice the rest. But contrary to his promise the said Mazerine did by break of day cause fourscore of these men to be barbarouslie murthered, who were all the informant’s friends and followers. Col. Campbell being angry at the murder, again demanded explanations, and Mazerine said he would give them before General Munro. He, however, fled to England and never appeared before General Munro, “but when he came to the parliament informed them that he had stormed a strong fort wherein there were many Irish and took it by force, for which he received £1000. Deponent will prove this murder by many credible witnesses.

Lord Massereene:

At the time when these men “complained to be killed” at Ballymoney alias McNachton’s fort, the whole Scotch army and some of the English regiments marched forth together, which being distributed near the mouth of the Bann river, Lord Massereene, Col. Campbell and Col. George Munroe’s regiments were ordered to scour the river of the Bann and Major-General Robert Munroe and the other party of the army the sea side. We intended so to clear that country of the rebels who daily infested Carrickfergus, Coleraine, Antrim and the other garrisons.

As the party was on the march, they, observing this fort, sent 500 men to take it. The reason why they wanted to take this fort was because it was the strength of those called “the bloody rebels of the Root,” who had committed many cruelties on the poor Protestants. They were then confidently reported to be the authors of the cutting off of the English regiment of Coleraine. This regiment had recently been encountered and defeated by the rebels and were fallen upon in their retreat by people from this fort.

When [Major] O’Connelly challenged the fort, it refused to surrender and stood on its defence. The whole narration about Lord Massereene having intercepted a letter from the fort to Col. Campbell is an invention “never heard of till now and dressed for the occasion”.

They in the fort refusing, O’Connelly’s party made ready for a storm. The enemy seeing that, and knowing the certain consequence, yielded unconditionally; and our men entering immediately bound the prisoners and pillaging the fort, found five or six of the colours of the Coleraine regiment that had been cut off by them before. All those supposed passages of O’Connelly coming to the fort in Col. Campbell’s name, of his promising protection, of his securing their lives and goods for them, fathered on Major O’Connelly, are, Lord Massereene believes, equally true with the story of the intercepting of the letter [so, are false].

The prisoners were brought by O’Connelly into the Leaguer and Lord Massereene, Col. Campbell and Col. Munroe being in the company, as he remembers, went to view them. They were put under the care of one Capt. Campbell, brother to Col. Campbell, who then had the guard, “and Col. Campbell speaking the Highland Irish with divers[e] of them,” finding as it appears by the sequel, some of them such as he either had kindness for, or intended to make use of, caused them to be kept apart and a little in front of the rest.

“And the officers being immediately gathered together to devise what to do with the prisoners, seeing they were brought alive (which was not usual at that time) there went off immediately 30 or 40 muskets, and they[, upon] calling to the sentinel at the tent door to inquire the reason, were told the soldiers had killed all the prisoners except a few, which proved to be those fifteen gentlemen Col. Campbell had set apart immediately before. This being done without any order that appeared, was then and often after resented by the Lord Massereene as most unhandsome, respecting the manner of the thing, though there was enough, seeing the English colours were found in their possession, to have brought them to a trial of court martial where they could not have escaped.”

On his inquiring for the case of the sudden killing, certain reasons were suggested:–

One was that they were men who were in a particular relation dependent to the MacDonnells and falling into the hands of the Campbells, “between whom there hath been an ancient feud, met with the fate which either sept gave the other coming under their power, for such hath been their constant practice, as is notoriously known.”

Another reason was that the finding of the English colours in their possession revived among the soldiers memories of the cruelties perpetrated on the poor soldiers and especially on those of Coleraine. Both these reasons were urged by the unruly soldiers, “because no quarter had been given before that time; nor, indeed, in some ears after on either side.” The Earl of Mount Alexander, Sir Henry Tichbourne, Sir Arthur Forbes, Col. Trevor, and all that served in the early part of that war will testify to this.

The information is quite inaccurate in stating that Lord Massereene went to England, reported alleged services, and got £1,000 from the House of Commons. The Journals of the Parliament will prove that no such grant was made to him.

About a year ago when Lord Massereene was attending the King in the matter of the Declaration for settling Ireland, Col. McNachton spoke about this matter with some resentment. Thereupon Lord Massereene in presence of Sir Arthur Forbes went to him, and informing him of the truth of the matter as is before recited, said that officers were now in town who had seen all that had happened and would corroborate Lord Massereene’s explanation. Col. McNachton went no further because, as Lord Massereene thinks, he knew there were men in London who could refute him. He has now again made absolutely false suggestions by his scandalous paper.27

It is difficult to fully ascertain what truly happened at Dunmull. Were John Macnaghten and his followers really Irish Rebels, or was Lord Massereene’s story simply a cover-up to protect the mutinous Campbells, or he and his peers’ own ruthless tactics? Military leaders of 1641-2 would regularly attempt to cover up their atrocities, so it would not be surprising if the discovered ‘colours’ were fabricated. However, Randall MacDonnell did apologise in a letter to General Munro:

I am sorry that in my absence my people were so unfortunate as to doe any hostile act, though in their owne defence, being compelled to it for safety of their lives, which they say they can make appeare in a convenient time[—]28

which would likely include the employees beneath him such as the Macnaghtens, as well as his other tenants.

MacDonnell himself was mostly undecided on his position in the conflict after his initial O’Neill alliance, preferring to take a neutral role; he even donated food and supplies to the Protestants of Coleraine whilst it was under siege by rebels, discretely sending a boat of supplies into the town via the Bann. However, other MacDonnells were involved in the rebellion, such as Sir James MacDonnell, a leader in the rebellion who took Clogh Castle, an important property of Randal MacDonnell’s being held for him by a Walter Kennedy, showing possible conflict of interest and even hostility within the family.29 The illegitimate stepbrother of Randal, Maurice, was also hung in 1643 for his involvement. The MacDonnells were Catholic Gaelic nobles, increasing the likelihood of a general affinity with the rebellion’s cause throughout the family, even after Randall MacDonnell distanced himself personally from the O’Neill cause.

Similarly, John Macnaghten appears to have remained a Catholic, whilst his brother Daniel and other siblings converted to Protestantism, evidenced by the fact they had no land confiscated by the government following the restoration; this again could hint at rebellion sympathy among unconverted Macnaghten family members.30

On one hand, Macnaghten’s Ballybogey fort could have been filled with the pro-rebellion John Macnaghten and a large band of family members and lay rebel forces. On the other hand, he could genuinely have been seeking to protect himself, caught in indecision between the opposing forces like his superior Randall MacDonnell, and providing a defensive position for his extended family and MacDonnell tenants.

A stones’ throw to Oldstone

The 1641 Deposition archives contain another identifiable relation of the Macnaghten family involved in a conflict; namely, in the taking of Clogh Castle. Clogh Castle was surrendered by Walter Kennedy to James McDonnell in early 1642: at nightfall, on the day of the castle’s surrender, an inhabitant named Margaret Dunbarr was visited by Alexander Starre and Neale McNeale on behalf of James MacDonnell, asking her for money, seemingly as a debt payment for his offer of protection to the protestants there.31 She said she had nothing to give. That night, her house was raided by rebels and stripped of everything it had. Starre was described by Dunbarr as ‘sonne in law to Alex McNaghtan’, who had the lease of multiple townlands around Clogh/Oldstone from Randall MacDonnell. Several Macnaghten family members held land there, and were named with the suffix ‘of Oldstone’.

Walter Kennedy had held Clogh Castle on behalf of Randall MacDonnell before its seizure, so it is possible that Alexander Starre was one of his staff members, a position acquired through his Macnaghten family connection, and was simply protecting himself by following the orders of its overthrower James MacDonnell. It is also possible that Starre took part in the rebellion under James MacDonnell’s leadership, much separated from the interests of his wife’s now-Protestant family — or even, under the same sway as his wife’s Catholic uncle John Macnaghten, who also held leases in Clough. While this account is an interesting addition to the complexity of the MacDonnell-Macnaghten web and their possible rebellion involvement, not much can be ascertained from this brief mention.

Whatever the case, the massacre at Dunmull was certainly tragic, though unprecedented only for the fact that Macnaghten and his followers were not killed immediately, as noted by Lord Massareene in his account. Henceforth Dunmull became known for the massacre, adding another layer to the history of this eccentric hummock.

The Rev. Hugh Forde noted that

A farmer named Mr. Todd, who lived to the age of 105, and died about the year 1870, got a great deal of information concerning these times from his father, who also died at an advanced age; he in his turn heard the story of the massacre from his father, who was a young man in 1641, reared near Ballywillin old church, and who remembered the massacre of Dunmull and the destruction of the fort and the old church of Ballywillin by General Munro.32

At some point in this century the ordination stones (discussed above) were cast from the top of the hill, but it is unclear when. It was possibly an act of iconoclasm by Munro’s Protestant forces when they were at the fort, as they similarly defaced St. Patrick’s Well and chair when they destroyed Dunseverick Castle that year.33

Outdoor mass?

In penal times, when Catholics were more harshly stripped of civil liberties and religious freedom from about 1650 to 1821, Toberdornan was occasionally a mass site. According to O’Laverty, it is unclear how mass was celebrated in the Dunluce area in this time, but it is known that after Randal MacDonnell moved to Ballymagarry House in 1668 the mass station was changed to there,34 but there were thereafter ‘also occasional Mass stations at Kennedy’s of Carnglass, and at Tubberdornan or Dunmull, as well as at Bushmills’.35 The description of ‘Tubberdornan or Dunmull’ could suggest that the top of Dunmull Hill itself became a mass site; secret outdoor masses were held at mass rocks or hills all throughout Ireland during penal times, so this is not unprecedented. One can also imagine that the various stones scattered on or around Dunmull in these times, which, according to David Craig, were associated with a saint, became a part of the practicing Catholics’ devotional life and sense of place.

Conclusion

Dunmull Hill is a brilliant example of how locations inconspicuous and unimportant to modern people are layered with fascinating historical and archaeological detail. There is more to be explored with this curious hill, including the history of its massive outdoor preaching meeting during the 1859 Revival, a beautiful folksong, and even a journey to Tír na nÓg.

Rev. Hugh Forde, ‘Portrush’ in Sketches of Olden Days in Northern Ireland: Including Portrush, Dunluce Castle, Dunseverick Castle, Ballycastle, Giant’s Causeway, Rathlin Island, Coleraine, Derry, Inishowen, Tory Island (Belfast, 1923); William Richardson, ‘A Letter on the Alterations that have taken place in the Structure of Rocks, on the Surface of the basaltic Country in the Counties of Derry and Antrim’ in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 98 (1808), p. 219.

Richardson, ‘A letter…’, pp. 221-2.

Angélique Day and Patrick McWilliams eds., Ordinance Survey Memoirs of Ireland 16: Parishes of County Antrim V 1830-5, 1837-8: Giant’s Causeway and Ballymoney (Belfast, 1992), p. 33; Forde, ‘Portrush’; W. J. Fitzpatrick, The Life of Charles Lever (London, 1879), p. 164.

Samuel Lewis, A Topographical Dictionary of Ireland (London, 1837) [Digitised] https://www.libraryireland.com/topog/ [accessed 28 September, 2024]; W. J. Fitzpatrick, Charles Lever, p. 164.

OS Memoirs 16, p. 33.

‘Rock-Basins, or ‘Bullauns’, at Glendalough and Elsewhere’, Glendalough Heritage Forum [Website] https://glendalough.wicklowheritage.org/topics/archaeology/rock-basins-or-bullauns-at-glendalough-and-elsewhere-published-in-1959 [accessed 14 December, 2024].

Elizabeth Fitzpatrick, Royal Inauguration in Gaelic Ireland c. 1100-1600: A Cultural Landscape Study (Woodbridge, 2004), pp. 116-7.

David Craig, Landmarks: An Exploration of Great Rocks (London, 1995), p. 297.

D. A. Chart ed. A Preliminary Survey of the Ancient Monuments of Northern Ireland (Belfast, 1940), p. 9; ‘Hillfort, Bullaun and Well: Dunmull’, Ariadne Portal [Website] https://portal.ariadne-infrastructure.eu/resource/c9c2394cb480875d8aee766f2c54165f5ceda947246a043de217a3b5d8915c15 [accessed 28 September, 2024]; Sam Henry, Dunluce and Giant’s Causeway: A Pot-Pourri of Facts and Fancies (Belfast, 1944), p. 15.

Fitzpatrick, Royal Inauguration…, pp. 115-6, 139; Chart, A Preliminary Survey…, p. 9.

Fitzpatrick, Royal Inauguration…, p. 138.

OS Memoirs 16, pp. 33-4; Fitzpatrick, Royal Inauguration…, pp. 115-6.

Ibid., p. 139.

Fitzpatrick, Landscapes of the Learned: Placing Gaelic Literati in Irish Lordships 1300-1600 (Oxford, 2023), p. 290.

Ibid., pp. 290-1

Ibid., pp. 290-1; T. E. McNeill, Anglo-Norman Ulster: The History and Archaeology of an Irish barony, 1177-1400 (Edinburgh, 1980), p. 120.

T. E. McNeill refers to mills in the townland of ‘Tiperdornan’ being ‘brought back into commission’ in the 1350s; no river or stream runs through the townland, so it could not have been a watermill. ‘Ballywillan’ is said by the O.S. Memoirs to possibly mean ‘mill town’, and a BBC article denotes its meaning as ‘The Town of the Mill’. (OS Memoirs 33: Parishes of County Londonderry XII 1830-5, 1837-8: Coleraine & Mouth of the Bann (Belfast, 1992), p. 52; Ronan Lundy, ‘History from Headstones’, BBC [Website] https://www.bbc.co.uk/northernireland/yourplaceandmine/antrim/ballywillan_graves2.shtml [accessed 24 October, 2024].)

Nearby Ballybogey also had a mill: as one of the witnesses in the 1641 Depositions, the Scottish George Tomson, was held captive there, with his Scottish companion William Loggan, by Irish rebels. The prisoners were taken to a hillfort in Ballyrashane after a few days and ordered to be hung; Tomson was spared and taken back to Coleraine, whilst Loggan was hung. (‘Examination of George Tomson’, 8 March, 1653, 1641 Depositions, Trinity College Dublin, MS 838, fols 069v-070v.) By 1716 the Ballybogey mill was a corn mill — so, likely had been a century before — and was granted in a lease to Alexander McNaghten esq. by the Earl of Antrim with the townland of ‘Ballyboggy’ itself (‘Lease from the Rt. Hon. Randal, Earl of Antrim to Alexander McNaghten Esq. of Benvarden...’, 20 September, 1716, PRONI, ref: D2977/3A/3/1/61; ‘Counterpart lease from Rt. Hon. Randal, Earl of Antrim to Alexander McNaghten Esq...’, 30 April, 1720, PRONI, ref: D2977/3A/3/1/66). It is highly likely that the present day residential area of ‘Mill Square’ in Ballybogey is where this mill was. No water runs through this area — only a small stretch of the Bush lies in the south-east of Ballybogey townland — so it was most likely not a watermill.

Fitzpatrick, Landscapes of the Learned…, p. 292.

Perhaps ‘imagined’ is unfair.

Fitzpatrick, Landscapes of the Learned…, pp. 290-2.; OS Memoirs 33, p. 35.

Robert Pentland Mahaffy ed. Calendar of the State Papers relating to Ireland preserved in the Public Record Office. 1660-1662. (London, 1905), p. 456.

State Papers 1660-1662, pp. 455-6.

State Papers 1660-1662, p. 457; James O’Laverty, An historical account of the Diocese of Down and Connor, ancient and modern (Dublin, 1878), 269.

There is confusion over whether ‘Shane Dhu’ was the first generation Macnaghten in Ireland, and that he had several sons, one of whom was John, or if he himself was John and the other ‘sons’ were truly his brothers — nevertheless, the family were employed by and tenants of MacDonnell. (Angus I. Macnaghten, The chiefs of clan Macnachtan and their descendants (Windsor, 1951), pp. 63-71.)

OS Memoirs 16, p. 119; O’Laverty, Diocese of Down and Connor, p. 267.

Benvarden has been named in secondary sources as a possible location for the fort. While Macnaghtens owned Benvarden since at least 1636, Benvarden House was not constructed until sometime after 1668; and it also does not have the added testimony of oral tradition. Ballybogey is the most likely site. (‘Benvarden House’, Causeway Coast and Glens Borough Council [Website] https://www.causewaycoastandglens.gov.uk/see-do/arts_museums/museums-services/ballymoney-museum/ballymoney-heritage/estates-and-stately-homes/benvarden-house [accessed 14 December, 2024]; Macnaghten, The chiefs of clan Macnachtan…, p. 66.)

State Papers 1660-1662, p. 455; Macnaghten, The chiefs of clan Macnachtan…, p 65.

State Papers 1660-1662, pp. 455-7; A Collection of some of the massacres, &c. committed on the Irish in Ireland since the 23rd of October, 1641 (London, 1662).

I have not included ellipsis in the quote here for the sake of readability, but only extraneous details have been removed.

‘The Earl of Antrims Letter to Generall Major MONROE’, A trve relation of the proceedings of the Scottish armie now in Ireland by three letters (London, 1642), p. 9.

‘Examination of Margarett Dunbarr’, 8 May, 1653, 1641 Depositions, Trinity College Library Dublin, MS 838, fols 237r-238v.

Macnaghten, The chiefs of clan Macnachtan…, p. 65.

‘Examination of Margarett Dunbarr’, 8 May, 1653, 1641 Depositions, Trinity College Library Dublin, MS 838, fols 237r-238v.

Forde, ‘Portrush’.

Read more about this in my post ‘Dunseverick’s Christian history and legends’ — https://curiosofirishhistory.substack.com/p/dunsevericks-christian-history-and

The MacDonnell’s had a private chapel at Dunluce, which likely served nearby Catholics in worship and sacraments.

O’Laverty, Diocese of Down and Connor, pp. 312-3.