Rosamond Praeger, a forgotten Irish poet

A sketch of her faith and cultural activism with a selection of her best poems

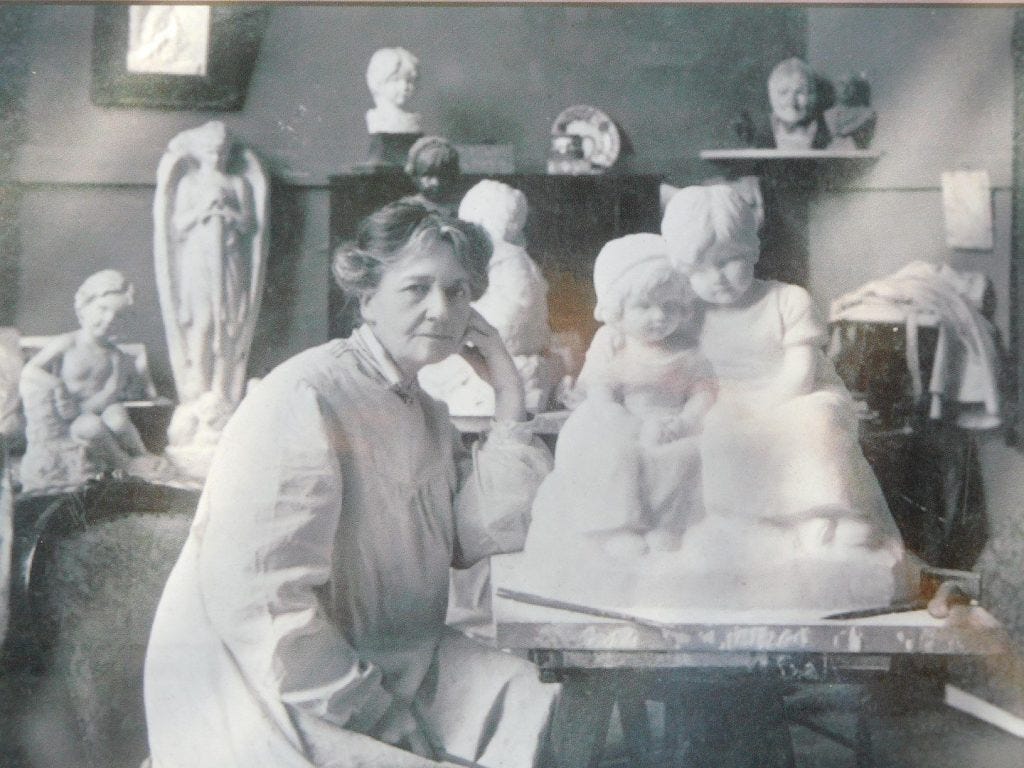

Sophia Rosamond Praeger (1867-1954) was an Irish sculptress, illustrator, and poet from Holywood, County Down. She is perhaps the best-remembered historical figure in Holywood. Her sculptures adorn prominent buildings throughout Belfast, such as St. Anne’s Cathedral, the Falls Road Library, and Queen’s University’s main Lanyon building; and her ‘Johnny the Jig’ is a prominent landmark in Holywood. Her sculpting style is immediately recognisable, often depicting children, in bas-relief or statuette form.1 Yet, public knowledge of her life and art is practically non-existent outside of Holywood.2 Her small body of poetry, which displays her religious faith and participation in the Celtic Revival, is even more neglected.

To put forward a small contribution to her legacy, I will discuss briefly her Christian background (in the Non-Subscribing Presbyterian tradition), her career and participation in the Celtic Revival and suffrage movement, and the culmination of these influences in her art, before providing a selection of the most noteworthy of her poems that I have come across. These have been drawn from Con Auld’s Rosamond Praeger: The Way That She Went.

Her faith and career

Rosamond Praeger and her family attended the Holywood First Non-Subscribing Presbyterian Church, which seceded from the mainline in 1704.3 The Non-Subscribing tradition goes as far back as the late seventeenth century, and led to various splits in Irish Presbyterianism over the requirement of members to subscribe to the Westminster Confession of Faith, eventually resulting in the formation of the Non-Subscribing Presbyterian Church as a denomination in 1910.4 As the tradition stressed non-creedalism, it is difficult to assert the beliefs of individual congregations, but there is a long tradition of Unitarianism — believing in a single-person God, instead of the Trinity as per orthodox Christianity — within the Non-Subscribing church.5 Con Auld, biographer of Rosamond Praeger, notes that her Praeger ancestors were among those in the ‘New Light’ camp who refused to subscribe to the Westminster Confession in the early eighteenth century.6 While it is difficult to ascertain whether the congregation was broadly Trinitarian or Unitarian, the influence of Unitarianism on Rosamond is, nevertheless, certain, as her mother, Maria Patterson, came from an explicitly unitarian background.7 The heterodox Praeger and Patterson families both being linen industrialists is consistent with provincial patterns in Ulster; the most influential families were typically non-Anglican dissenters, as can be seen in the rise of the Presbyterian middle-class in the late-nineteenth century, and in the prominence of Unitarians and Quaker families in the linen trade.8

Due to the sparsity of writing left behind by Rosamond Praeger, besides her children’s books and poems, it is difficult to assert her personal doctrinal beliefs.9 Whatever way Rosamond Praeger’s faith can be defined, it appears to have remained consistent, as she later became a teacher in the Holywood Non-Subscribing church’s Sunday school, wrote religious poetry, and remained a congregant until her death.10

Praeger’s career did not begin until her mid-20s, after she completed her art education in London.11 At first, she made her living from commissions for print illustrations more than from sculpture, and from her children’s books, which she both illustrated and wrote.12 She soon became involved in the vibrant milieu of activism which characterised the middle- and upper-class female public activity of late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century Ireland, moving amongst circles like the Temperance Alliance, the Belfast Naturalists Field Club, the Irish Women’s Suffrage Federation, and the Gaelic League.13 She illustrated and designed posters for these groups, hosted sculpture exhibitions through them to raise money, and illustrated publications like the newspaper Shan Van Vocht and various books by the Gaelic League.14 She also engaged in folklorist work, illustrating and publishing a collection of ‘Brian O’Lynne’ folksongs titled The olde Irishe rimes of Brian O’Linn (1901), and in 1933 the Folklore of Ireland Society journal, Béaloideas, published her ‘Rimes and Riddles from County Down’, which she collected from ‘Miss Lizzie Simpson, of Ballynahinch, County Down’.15 One of her most beautiful pieces, depicting the myth of The Fate of the Children of Lir, reflects her interest in Irish culture revival:

One of Praeger’s finest poems, ‘Home Sick’, from her time in London, reflects an even earlier interest in Irish culture and language, predating the Gaelic League (formed 1893). Its repeating phrase ‘Gradh-mo-chridhe’ translates to ‘Love of my heart’, dramatising her longing for Ireland;

Among these English hills and dales,

Oh Gradh-mo-chridhe, I stand.

The sunny fields, the shadowy vales,

Are spread on either hand.

My eyes say: Here is loveliness

My heart says — “Not to me”.

My heart is sick for Ireland, Gradh-mo-chridhe.16

Joseph McBrinn notes that by 1910, she became intensely interested in the theme of ‘the childhood of Irish saints’, and sculpted a series of both child and adult versions of different saints.17 This seems to reflect a culmination of her personal faith, her prior sculpting work for churches and graveyards, and influences from the Celtic Revival’s focus on Irish history and the hagiographic tradition. The saints she depicted include St. Patrick, St. Brigid, St. Fiachra, and the non-Irish St. Francis of Assisi.

While Catherine Gaynor analyses the abundance of children (and mother and child) depictions in Praeger’s work as self-imposed femininity, it could also be interpreted as a culmination of both her faith and her cultural and political interests.18 While the root of feminism pushed for social and political egalitarianism between genders, the Irish suffrage movement remained broadly bound to complementarian views, as many suffragists were still Christian, and the mainline Irish churches broadly rejected suffrage on the grounds of its egalitarianism being unbiblical.19 Most also retained a passive approach: suffragette militancy came to Ireland from England quite late, largely through the Women’s Social and Political Union, who pushed the Irish Women’s Franchise League toward similar violent tactics; however, they were both condemned by the increasingly popular anti-militancy umbrella group, the Irish Women’s Suffrage Federation.20 For many suffragists, the vote would be an extension of the central feminine roles of mother and wife, not a radical subversion of biblical principles, in theory or in tactic.

Many female Gaelic Leaguers also saw the importance of motherhood for the reviving of Irish culture. Mary Butler, for example, argued that

respectable Irish women could still make a significant contribution to building an independent Irish nation through activities undertaken within their own homes. Besides bringing up their children to speak the national language, Irish women could also teach them pride in the national history, immerse them in Irish culture, and purchase household articles of Irish manufacture.21

At the root of these principles was Christianity. The undergird of personal faith, combined with the principles of conservative Biblical femininity, as shared by many suffragists and Gaelic Revivalists, perhaps partly explains Praeger’s primary motif of children, and the mother-child image. Its reminiscence of depictions of the Mother of God bearing the infant Christ, so prominent in Catholic Ireland, also cannot be ignored. As so little of Praeger’s writing has been preserved, it is difficult to assert any interpretation with absolute certainty. Her works must speak for themselves.

Her poetry

As most of Praeger’s poetry is from her Old fashioned verses and sketches, much of it is comedic, often featuring an Ulster Scots dialect. Poems such as ‘Old Kate and her Friend’, for example, features old women complaining about youngsters wearing too much makeup:

“Girls, do you say? I tell ye Kate,

The girls that’s in it has got me bate.

You an’ me now, had cheeks like roses.

We had no call to whitewash our noses!”22

Other poems reflect, however, a more sober look at social issues, often regarding children, and are somewhat reminiscent of William Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Experience in their pithiness. These expressions are undoubtedly closely tied to the concern for child welfare which was a part of the milieu of Irish women’s activism. For example, the suffrage- and nationalist-adjacent group Inghinidhe na hEireann (Daughters of Ireland), founded by Maud Gonne, made providing meals for school children one of its central operations, alongside the promotion of ‘Irish-Ireland’ principles.23 Social reform and education was also an important part of the Non-Subscribing Presbyterian tradition Praeger came from.24 ‘Old Maggie’s Lament: Condemned by the Sanitary Inspector’ comments on the disruption of domestic life caused by Irish Sanitary Officers and their ‘blunt’ reports:25

“It’s never again I’ll sit by my door

Where many a time I have sat to spin;

An’ I’m lost for the want of my own wee place

Where I wish to God they had let me be.”26

Another poignant verse, effectively employing a broken and rhymeless common metre, bemoans the poverty of Belfast children:

The children play on the pavement.

Where are the flowers of April?

Where is the summer grass?

Where are the sands and daisy fields

Where happier children play?

Oh turn your heads, ye careless ones

And hear the children cry.27

Other poems engage more plainly with the traditions of lyrical and pastoral poetry, often focusing on her native Holywood landscape, laden with otherworldly language and references to local placenames. It is in these poems we see the furthest extent of her literary engagement with the the Irish Literary Revival. One of these, ‘The Song of the Streams’ — perhaps her best poem —I have included below.

Her most religious poems were written during World War Two, perhaps due to how (literally) close to home it was. In 1941 the Belfast Blitz took place, wherein thousands were killed and injured during an enemy air raid; ‘from her eyrie in the Craigavead hills, Rosamond saw the blood red sky and wept for her people.’28 She had already lost a brother in the First World War, and had sculpted many war memorials, in Holywood and elsewhere in Ulster.29 Perhaps her faith was strengthened by these tragedies; hence the more frequent turn to religious expression in verse by the 1940’s.

Selected poems

I have included below ten poems. While some are of a meandering quality, I believe their sentiment, and frequent beauty of expression, makes them worth including.

Song of the Streams30

To A. W. G.

If I go gently from this world

And lie in a trance of dreams,

I know that the music I shall hear

Is the song of the little streams.

The lovely song of the rippling streams

That leave the hills of Down,

And singing, slip by the bracken slopes,

And the fields of green and brown.

The song they sing is the robin’s song,

Gay, with a hint of sorrow,

As if they dream of the land they leave,

And the ocean of tomorrow.

If I go smiling from this world,

You will know I am hearing then,

The liquid chant of a lilting burn,

In the lap of an Ulster glen.

The Cynic31

“Summer is y-comen in”

Now the jollities begin!

Earwigs in the garden bower

Slugs within the cauliflower,

Wasps y-stickin in the jam,

Flies y-sittin on my nose,

Green ones on my rarest rose,

Midges everywhere that cool is,

Moths among my winter woolies.

Daddies on the supper-table

Leaving legs where ever able,

Weeds y-sprouten on the path,

Spiders floating in my bath,

Rabbits eating all the greens,

Mice y-nesten in the beans,

Corncrakes cheering up the night,

Clegs y-sitten down to bite.

Summer is y-comen in,

Now the jollities begin.

A Song of 194032

I’m going up the mountain to a place I know,

Up above the Valley where the blackthorns grow,

For the roads are dark and haunted down below.

There through the mosses the young streams creep,

Small birds will pipe to me, small flowers peep,

There in the quiet the great stones sleep.

I’m going up the valley when the blackthorns blow,

Nobody will follow me, nobody will know,

There will be healing, as there was long ago.

The Leafy Lanes of Holywood33

The leafy lanes of Holywood

Go winding here and there;

And none can tell me where they go,

And no one seems to care.

But in them walks the Spirit of Peace,

To breathe the kindly air.

Maybe you meet a straying ass,

Or a goat that’s pulled its tether.

Or in a primrose time, or berry time,

A two-three weans together.

But you will find a blessing there

In any kind of weather.

For heartsome are the golden whins

That crown the banks in May.

And heartsome are the golden wreaths

That deck the Autumn day.

And dear the little twinkling burns

That run beside your way.

The leafy lanes of Holywood

Have many a dip or bend,

And none can tell you whence they come

Or where they mean to wend.

Perhaps they lead to Eden.

Could we but reach the end.

The Wind34

Our silly brains are sick with crowding fancies,

Our silly hearts are full of phantom ills—

The Wind of God is blowing from the hills.

Trust in the Wind of God.

Great spiders gather in the holy places.

The light is sullied by the webs they weave—

The Wind of God will banish them at eve,

Trust in the Wind of God.

The smoke of funeral pyres has blackened Heaven

We decorate the House of Life with shrouds.

The Wind of God is scattering the clouds.

Trust in the Wind of God.

We make us chains to keep our feet from mounting,

We build us prisons to keep out the day—

The Wind of God shall sweep them from its way.

Trust in the Wind of God.

The fear of pain is in our broken breathing,

Our eyes are dim—Oh, dim with coward tears.

—The Wind of God is blowing down the years,

The Wind of God is shattering our fears.

Trust in the Wind of God.

Home Sick

Among these English hills and dales,

Oh Gradh-mo-chridhe, I stand.

The sunny fields, the shadowy vales,

Are spread on either hand.

My eyes say: Here is loveliness

My heart says — “Not to me”.

My heart is sick for Ireland, Gradh-mo-chridhe.

Why does the wind no comfort bring

When wandering thro’ the calm?

Why does the song the rivers sing

Drop not the wonted balm?

My ears say “Hark! a melody!”

My heart says “Not to me”.

My heart is sick for Ireland, Gradh-mo-chridhe.

I lay me where the grass is soft

And linnets come and go.

The little wood-flies dance aloft.

The blackbird’s pipe is low.

I say “The peace I seek is here”.

My heart says “Not to me”.

My heart is sick for Ireland, Gradh-mo-chridhe.

I reason hotly with my heart.

“What are you asking more?

Why do you now forget your part—

The rapture felt of yore?

The glory of the earth is here!”

My heart says “Not for me”.

Oh! I am sick for Ireland, Gradh-mo-chridhe.

War35

I hear the soldiers marching on the road,

And overheard their grim machinery roars.

Wild lights go flickering across the world,

And Death is knocking on a million doors.

And this is Easter. Lovely, delicate things

Are pushing upwards through the warming earth,

The resurrection of the hidden Power,

That fosters in us life, and love and mirth.

What is the darker Power that dogs us here,

And piles on Man intolerable loads?

I see the war-planes crashing from the clouds,

And mangled men upon a thousand roads.

Dawn36

There is no joy in this grey dawn,

That breaks upon the earth.

We know not what the day will bring—

What agony of dearth;

What black morass to struggle in,

Or what portentous birth.

Yet low on the horizon edge

A light is coming back.

Could but the nations see thereby

To find the narrow track.

The Spirit of God still moves above

The battle and the wrack.

Let There Be Light37

The lights go up. Thanks be to God,

The lights go up once more.

They signal from the distant hill,

They march along the shore.

Heralds of peace, they call to us,

“The Terror by Night is o’er!”

O Light of Lights, be with us now!

Shine on our clouded path.

We know not to what bourne we wend,

Or what the future hath.

Man, who has wrecked thy fruitful earth,

Must bide the aftermath.

Down the Road38

On down the road we go,

On down the road;

Each with our playthings,

Each with our load;

Leaving behind us

The seeds we have sowed.

Some sow happiness,

Some sow pain,

Some sow nothing-at-all,

But grumbling at the rain.

Some sit to rest awhile,

And never rise again.

On down the road we go,

Hiding each scar.

Some of us gazing at the mud,

Some at a star.

God help the whole of us,

Such as we are.

Joseph McBrinn, ‘Praeger, Sophia Rosamond’, Dictionary of Irish Biography. https://www.dib.ie/biography/praeger-sophia-rosamond-a7472 [accessed 22 August, 2024]

Joseph McBrinn, ‘‘A Populous Solitude’: the life and art of Sophia Rosamond Praeger, 1867-1954’, in Women’s History Review 18, no. 4 (2009), pp. 577, 581.

Con Auld, Rosamond Praeger: The Way That She Went (Holywood, 2006), p. 44; Heather Walker, ‘First Presbyterian Non-Subscribing Church c. 1700-2010’ in James Robinson, Heather Walker, and Janet Taylor, Presbyterianism in Ulster 1613-c.1865: A regional study with particular reference to Holywood, Co. Down (Holywood, 2015), pp. 183-4,188.

Heather Walker, ‘First Presbyterian Non-Subscribing Church c. 1700-2010’ in James Robinson, Heather Walker, and Janet Taylor, Presbyterianism in Ulster 1613-c.1865: A regional study with particular reference to Holywood, Co. Down (Holywood, 2015), pp. 183-4,188.

‘Why were we called Unitarians? Why are we no longer called Unitarians?’, Dromore Non-Subscribing Presbyterian Church https://www.dromorensp.church/sermons-and-blog/why-were-we-called-unitarians-why-are-we-no-longer-called-unitarians [accessed 23 August, 2024.]

Auld, Praeger…, p. 44; Walker, ‘First Presbyterian Non-Subscribing Church…’, pp. 183-5.

Andrew O’Brien, ‘Patterson, Robert’, Dictionary of Irish Biography. https://www.dib.ie/biography/patterson-robert-a7234 [accessed 22 August, 2024]. I was unable to glean from Heather Walker’s article (previous footnote) whether the ministers throughout the history of the First Presbyterian Non-Subscribing Church in Holywood were Unitarian or not.

Alvin Jackson, ‘Irish unionism, 1870-1922’ in D. George Boyce and Alan O’Day eds. Defenders of the Union: A survey of British and Irish Unionism since 1801 (London, 2001), pp. 115-6; Davidoff, Leonore, and Catherine Hall, Family Fortunes: Men and Women of the English Middle Class 1780-1850 (Milton Park, 1987), p. 73; Richard S. Harrisson, The Richardsons of Bessbrook: Ulster Quakers in the Linen Industry (1845-1921) (Dublin, 2008).

McBrinn, ‘‘A Populous Solitude’…’, p. 579.

Auld, Praeger…, pp. 44, 70.

Ibid., pp. 47-8.

Auld, Praeger…, p. 50

Ibid., pp. 51-5; McBrinn, ‘‘A Populous Solitude’…’, pp. 580, 586-7

Auld, Praeger…, p. 50; McBrinn, ‘‘A Populous Solitude’…’, p. 580.

S. Rosamond Praeger, ‘Rimes and Riddles from County Down’ in Béaloideas 8, no. 2 (1938), p. 171.

Auld, Praeger…, p. 48.

McBrinn, ‘‘A Populous Solitude’…’, p. 584.

Catherine Gaynor, ‘An Ulster Sculptor: Sophia Rosamond Praeger (1867-1954)’ in Irish Arts Review Yearbook 16 (2000), p. 36.

Diane Urquhart, Women in Ulster Politics 1890-1940 (Dublin, 2000), pp. 117, 203; Dana Hearne, ‘The Irish Citizen 1914-1916: Nationalism, Feminism, and Militarism’ in The Canadian Journal of Irish Studies 18, no. 1 (1992), p. 9; Davidoff, Leonore, and Catherine Hall, Family Fortunes: Men and Women of the English Middle Class 1780-1850 (Milton Park, 1987), p. 116; Myrtle Hill, ‘Divisions and Debates: The Irish Suffrage Experience’ in Blanca Rodriguez Ruiz and Ruth Rubio Marin eds. The Struggle for Female Suffrage in Europe: Voting to Become Citizens (Leiden, 2012), p. 266.

Urquhart, Women in Ulster Politics…, pp. 28-32; Margaret Ward, ‘‘Suffrage First, Above All Else!’ An Account of the Irish Suffrage Movement’ in Feminist Review, no. 10 (1982), pp. 24-5.

Frank A. Biletz, ‘Women and Irish-Ireland: The Domestic Nationalism of Mary Butler’ in New Hibernia Review 6, no. 1 (2002), p. 61.

Auld, Praeger…, p. 119.

Senia Paseta, Irish Nationalist Women, 1900-1918 (Cambridge, 2013), pp. 115-9

Walker, ‘First Presbyterian Non-Subscribing Church…’, p. 185.

See: Joanne Rothwell, ‘The Significance of the Sanitary Officer’, History Ireland 31, no. 2 (2023). https://www.historyireland.com/the-significance-of-the-sanitary-officer/ [accessed 22 August, 2024]

Auld, Praeger…, p. 120.

Ibid.

Ibid., p. 67.

McBrinn, ‘‘A Populous Solitude’…’, p. 580.

Ibid., p. 17.

Ibid., p. 27.

Ibid., p. 33.

Ibid., pp. 36-7.

Ibid., p. 45.

Ibid., p. 65.

Ibid., p. 66.

Ibid.

Ibid., p. 88.